One of the reasons that I treasure the writings of the French Reformer, John Calvin, is the pastoral heart that shapes his reflections so profoundly. Deeply and personally acquainted with sharp and prolonged suffering of many kinds, Calvin knew that, under the weight and strain of our many cares, the best help for God’s afflicted people, as Psalm 94 puts it, is to consider the consolations of God: who he is in his majesty and condescension, what he has done in his mercy and kindness, and what he promises to do always in his steadfast love and faithfulness.

Christianity rests upon these consolations. Our faith grows by these consolations. And Calvin, ever the pastor, knows to turn his flock again and again to these courage-forming, Christ-centered comforts of God.

One passage from Calvin that I especially cherish is found in his 8th sermon on Deuteronomy where he reflects upon God’s reminder that he carried his people through the wilderness as a man carries his son. And here it is in all the quaintness of the original 16th century English translation:

But yet the similitude that Moses useth where he sayth, as a father beareth his childe: deserveth to be well weyed. Truely if there were no more but this, that God compareth himself with a fleshly father: it were a singular record of infinite and incredible love. What a one is GOD if he be taken in his majestie? Are wee worthie to come to him so familiarly? Now then seeing hee taketh upon him the person of a man, and a creature, and lykeneth himselfe to them that beare their children: therein we see how he humbleth himselfe, of good wil to accept us in like case as if we were his owne children. And what a token of love is that? Now as for us, wee be nothing woorth: needes then must wee acknowledge an inestimable goodness in our God, when he putteth off his majestie, to make himself lyke a man….What is to bee done then? Seeing that our GOD sheweth himself so loving and kinde hearted, that he protesteth himself to bee as a father towards his little babes, in bearing with our feeblenesse and infirmities: and seeing that he saith by his Prophet Esay, that although all the mothers in the world should forget their children, yet would not he forget us: and seeing he stoopeth so lowe as to liken himself to an Eagle and to a Henne, to shewe that he taketh us for his chickins and birdes: let us looke that wee yeelde unto him, and lay our selves as it were in his lappe, praying him to beare us and to releeve our infirmities, that we may be comforted at his hand, as he is readie to doe, if wee flee to his mercie for succour.

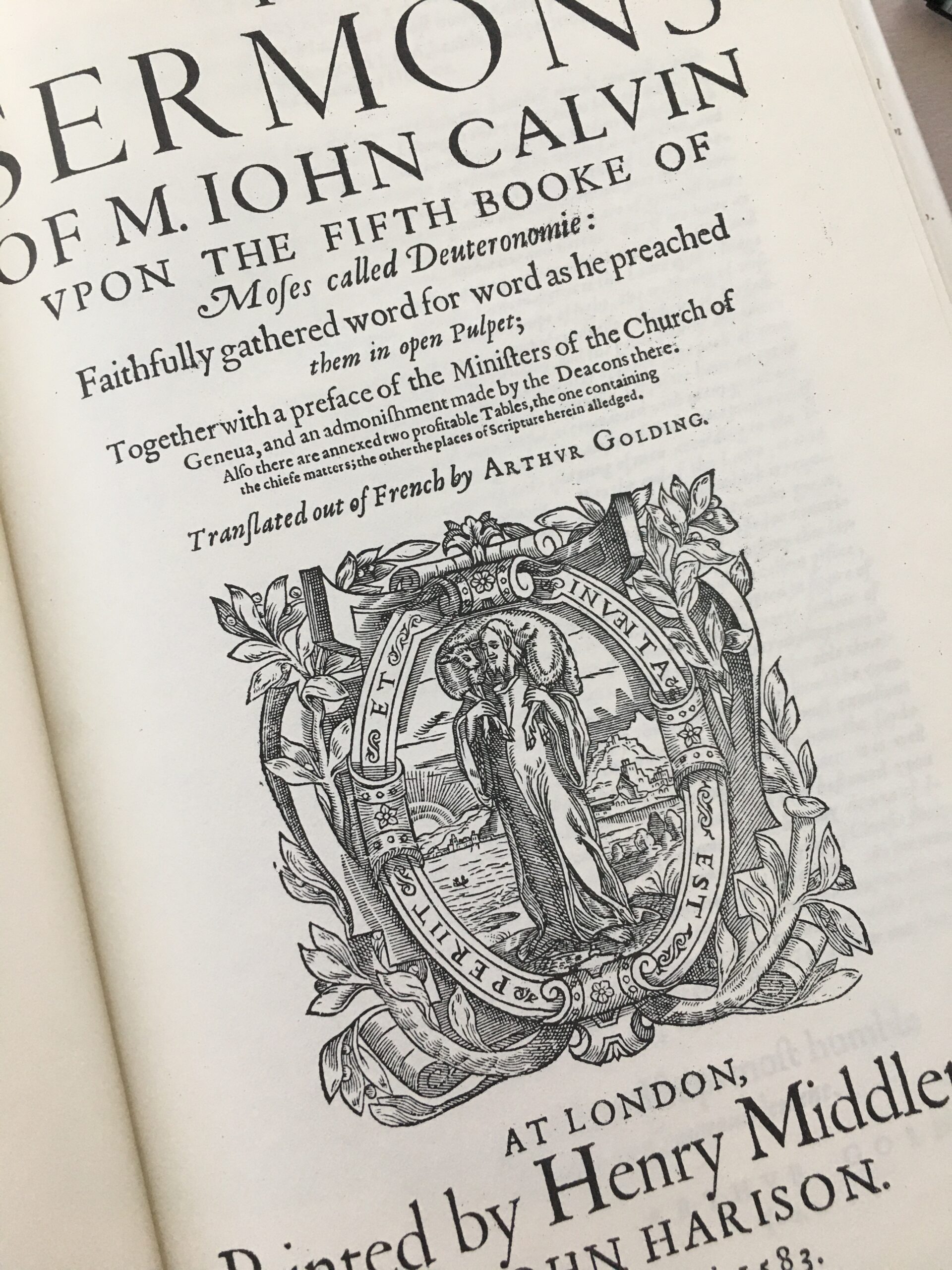

John Calvin, The Sermons of Master John Calvin upon the Fifth Booke of Moses Called Deuteronomie

Calvin piles up the biblical imagery to render a compelling picture of God’s covenant faithfulness. But for me the image of the “chickin” stands out. In our contemporary idiom, being a chicken is something clearly shameful, a metaphor of cowardice. But in the idiom of Scripture, being a chicken does not connote cowardice or suggest shame, but rather it is a rich image redolent with the comfortable thoughts of solace and satisfaction: the chicken in God’s Kingdom is that one who is gathered by Christ under the shelter of God’s wings to find hope and to gain courage in the eternal consolations of God.

In the reality of our wildernesses and trials today, how encouraging it is to hear Moses and his expositor Calvin say to us with great tenderness and compassion: there is no one like your God, bearing with your weakness, condescending to lay you as an infant in his lap, ready to comfort you and relieve you in all of your distresses, vowing never to forget. What a God! What a Gospel.

“For the Lord will not forsake his people; he will not abandon his heritage.” Ps 94:14

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit. As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be. World without end. Amen.

With you as God’s chickin,

Pastor Jon